Spanish slates and UK slates: a brief comparison

Nowadays, Spain is the main producer of roofing slate in the world. The fine-grained, smooth and durable Spanish slate has spread to all countries. However, this was not always so. There was a time in which the United Kingdom was a global power in roofing slate production. Roofing slate has been quarried since centuries in the UK, but it was during the Industrial Revolution, in the 18th century, when the quarries adopted the new technology and became the largest in the world in terms of production.

In contrast, the leading Spanish roofing slate company in the world, CUPA PIZARRAS, opened its first quarry in 1892. For decades, the production was mainly used by locals, but it was during the 60´s of the 20th century when this outstanding roofing slate burst into the European market. Both countries are major players in the roofing slate world. Nevertheless, today I am not writing about the interesting history of the roofing slate industry in these countries. Instead we’ll take a look at the singularities of roofing slates of these two countries.

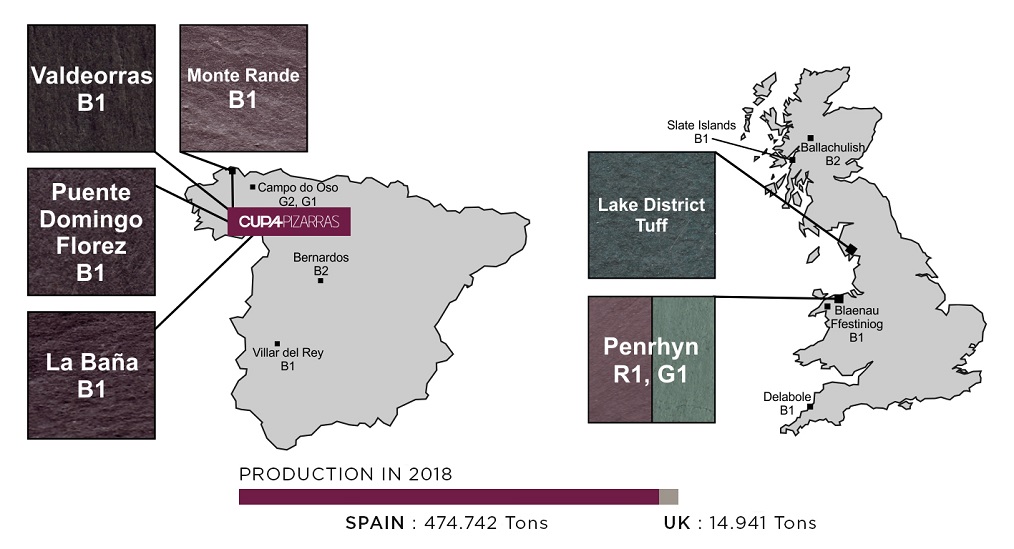

Most important roofing slate districts in Spain and the UK. The code for each district refers to the color of the rock quarried: B for black slates, G for green slates, and R for purple-red slates, while numbers refer to the type of rock, here 1 is for classic slate and 2 for phyllite.

In the UK there are several outcrops, each of them with its own character. In Scotland the most important outcrops are Ballachulish and the Slate Islands. Ballachulish slate is actually a grey, rough phyllite, widely used in the Scottish Heritage. These quarries closed in the 50´s, being this gap filled with Welsh and (mainly) Spanish roofing slate. The astonishing Slate Islands are located in the SW coast of Scotland. These islands were mined for centuries. The old mine pits are nowadays flooded by the sea, creating an extraordinary landscape. The slate from these outcrops is blue-black, with occasional pyrite cubes that can reach several millimeters edge.

Just below the Scottish boundary there are the outcrops of Lake District, where you can find a grey to green rough roofing slate. Again, this rock is not really a slate but a tuff, a rock made of volcanic ashes that developed a cleavage good enough to allow splitting into tiles. But is in Wales where lie the biggest outcrops of the UK. The Penrhyn roofing slate quarry, in Dinorwic will cut off your breath. These quarries, nowadays abandoned, were the largest in the world by the end of the 19th century. There you can see the exclusive purple and green slates, solid and durable but hard to split. These colors are the results of the environmental conditions during the slate sedimentation, and are very typical for the Welsh slate.

View of the slate roof of the Management Centre of Bangor University, made with slate from the Penrhyn quarry.

Not so far from there is the quarry of Blaenau Ffestiniog, which produces a black-blue slate with scattered iron sulphides. Wales keeps a rich industrial heritage related to roofing slate industry, which has been taken advantage of by the local government to promote a touristic model focused on the slate industry. Finally, in Cornwall, there is the quarry of Delabole, which produces a dark-grey slate, occasionally of green hue.

On the other hand, Spain does not have the same diversity of colors and rocks used as roofing slates than the UK, but instead has the biggest roofing slate outcrops of the world, the Truchas Syncline, a geological megastructure located in the NW of the Iberian Peninsula, between the regions of Ourense and León. The Truchas Syncline comprises the roofing slate districts of Valdeorras, Puente de Domingo Florez and La Baña. Roofing slates from these districts roofing slates are black to grey, fine-grained and homogeneous, with a perfect and regular cleavage, in other words, a classic slate as is defined in the geology manuals. Surface texture and brightness depends on the quarry. It can range from smooth and silky to rugged and grained, sometimes with a clearly perceptible lineation called hebra. The weatherable minerals are scarce and usually discarded during the fabrication process. In the last years, this process has been greatly improved with the incorporation of the lasts technological advances.

The Copenhagen Station was reroofed using CUPA 12, being a good example of how Spanish roofing slate can adapt to any urban landscape.

As pointed before, CUPA PIZARRAS started its long journey in the roofing slate business “only” more than 120 years ago, with the Solana de Forcadas historical quarry, in the mining district of Puente de Domingo Florez. In the following decades, the company opened several quarries in the other mining districts of the Truchas Syncline. But not all the roofing slate quarries are found in this area. In the N coast, there is the mining district of Monte Rande, in the region of A Coruña, and just few kilometers NW the Truchas Syncline you can find El Caurel. Roofing slates from these districts are very similar to those from the Truchas Syncline. Down to the South, in Extremadura, is the mining district of Villar del Rey, which produces black roofing slates. Only in a couple of minor outcrops you can find different roofing slates, in fact phyllites. In Campo do Oso (Lugo) there is a small production of green and grey phyllite, while in Bernardos, to the NW of the city of Madrid, there are also some outcrops of grey phyllites.

In summary, roofing slates from the UK are diverse, of the three color families (black, green and red-purple) found in roofing slates. Different types of rocks are also used (phyllites, tuffs, real slates). This diversity was created because of the geological history of the country. Usually, these roofing slates are coarse-grained, so tiles are thicker than those used in the Continent. Only a few quarries are working nowadays in the UK.

Spanish roofing slates are black, flat and regular, can be produced in any imaginable format, and are mostly free of weatherable minerals. This is also a result of the Spanish geological history, but we’ll see this in a future post.