Phyllite vs. slate: differences and characteristics

There has been increasing talk over recent years of phyllite as a kind of Premium roofing slate, with better technical and aesthetic characteristics than traditional slate, and of it being much more exclusive because there are only a few deposits in the world. Phyllite is progressively gaining prestige, but is this prestige deserved? Are we really looking at a rock with better characteristics?

First let us see what a phyllite is. The name itself already gives a clue about its nature. Phyllite refers to a group of minerals, the phyllosilicates, which are very abundant in the earth’s crust. As the name indicates, they have a flat, sheet form (phyllon, meaning sheet in Greek). In addition to phyllosilicates, it has other minerals in its composition: quartz, feldspar and sometimes small amounts of carbonates and iron sulphides.

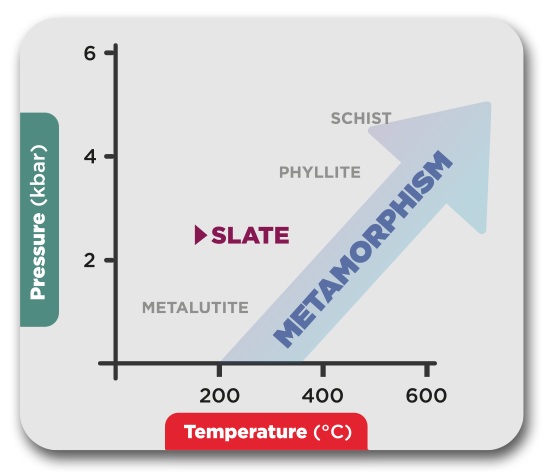

Like slate, it is also a metamorphic rock, the result of the chemical and mineralogical changes slowly taking place over millions of years deep in the Earth. A quick, intuitive way of understanding metamorphic processes is to think of them as an enormous oven, let us call it “nature’s oven”, where pressure and temperature act on the rocks.

Metamorphic series of “roofing slates”, from metalutites, of a lower grade, to mica-schists, of a higher grade. The rocks that give the best result are slate and phyllite.

The ingredient that needs to be introduced into this oven to obtain slate for roofing is clays. The clays have been transformed after a time, and what you get is slate. If you wait a little longer, what you will have will be phyllite. A little more and you will get mica-schists, a type of rock that can only occasionally be used as slate roofing, but we will talk about that on another day.

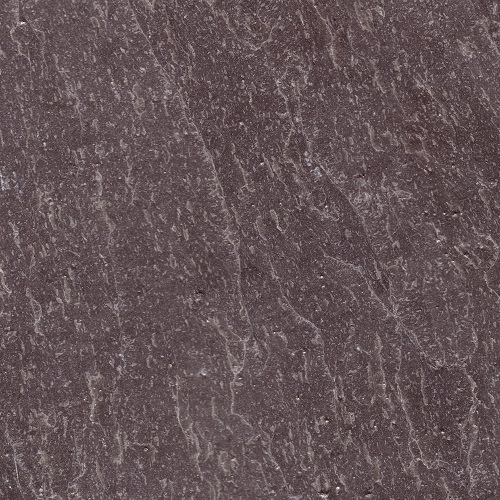

So, slates and phyllites have common properties. They are only differentiated by the higher metamorphic grade of the phyllites. However, this small increase in metamorphism makes phyllites and slates different. The first difference is the greater crystallinity of phyllite. The higher metamorphic grade means that the minerals created during this process are more developed and larger in size. The surface of phyllite is brighter than that of slate, showing characteristic small crystalline scales.

A consequence of this greater crystallinity is lower porosity, which translates into lower water absorption than with slate, which is already low. Approximate water absorption values are 0.2% for phyllite and 0.4% for slate.

From a mechanical point of view, phyllite is more fragile than the slate, precisely because of this greater crystallinity. The flexural strength of phyllite is approximately 50 MPa, compared to the 60 MPa typical of slate. Even so, these values are well within the minimums required for roofing slate.

These then are the differences. The rest of the construction properties of phyllite are similar to those of slate: high fissibility, enabling production of the thin, regular tiles used on roofs, density of around 2.7 g/cm3, impermeability, fire resistance and, above all, durability. Both rocks have similar values and can last for several hundred years under ideal conditions, far exceeding fifty years under normal conditions.

Left image: typical slate texture, fine-grained and homogeneous. Right image: phyllite texture, where the superficial scales can be seen, resulting from the higher metamorphic grade.

So, is it better to have phyllite than slate as a roofing material? In my view, the two rocks offer similar performance. The differences in physical and construction properties are small, and do not represent an advantage or disadvantage for either of them.

The aesthetic aspect is another matter. Here there are appreciable differences. As a general rule, phyllite is brighter than most slate varieties. This brightness is strongly influenced by the direction of the rock fibre or grain, coinciding with the length of the slab. This means that its appearance varies depending on the angle of incidence of the light.

This effect is also noticeable in other slate varieties and is an aesthetic feature greatly appreciated by some architects. It should not be forgotten though that what makes a rock good or bad is not the rock itself, but the use it is given. It is very important then to follow experts’ recommendations and, above all, to work with reliable companies that provide good after-sales service.