Natural slate in the Roman Empire

Slate is certainly an exceptional material. Its physical, mechanical and structural properties make it unique and there is no other rock in nature which brings together so many favourable characteristics for a variety of uses. For prehistoric societies, which did not have factories or industries to provide homogenous and regular building materials, slate was a real Swiss army knife, due to the amount of uses it could be given.

The Roman civilization, the basis of the Western world as we know it, was the first to extract, work, transport and install standard sized slate on roofs. It was worked regularly in areas where there were slate deposits.

Excavations of the Roman villa of Abermagwr where part of the slate layer can be seen. Original image in Davies and Driver, 2018. “The Romano-British villa at Abermagwr, Ceredigion: excavations 2010–15”

In his writings, Pliny the Elder mentioned the existence of slate in Liguria, close to Genoa, although he did not describe quarries or regular quarrying of this rock. However, the Roman archaeological site where the use of slate roofing has been recorded in most detail is not in Italy but rather in South Wales, in Ceredigion.

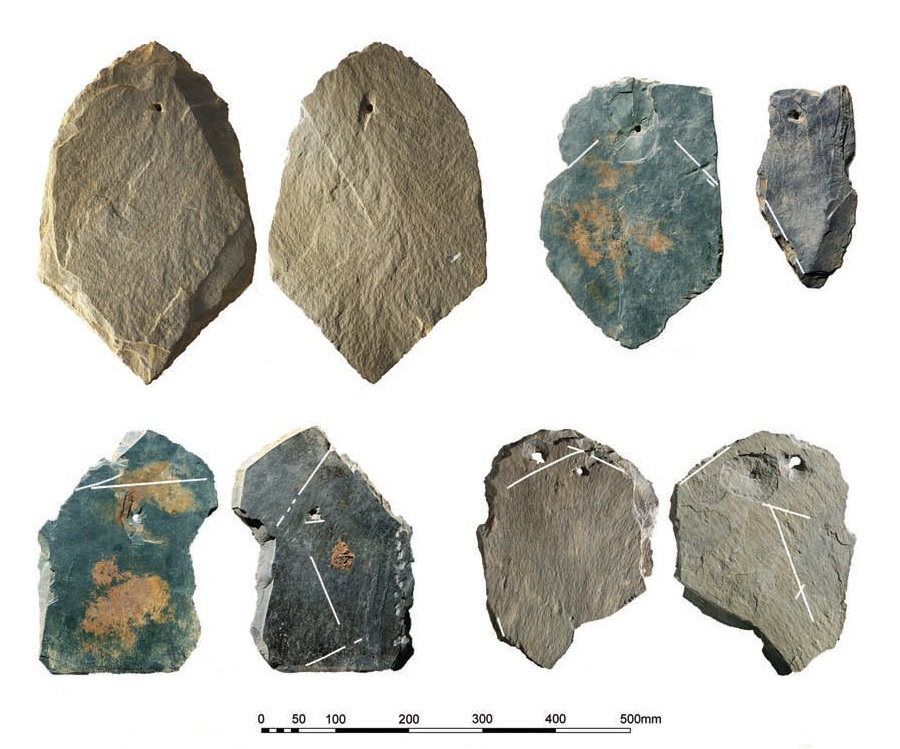

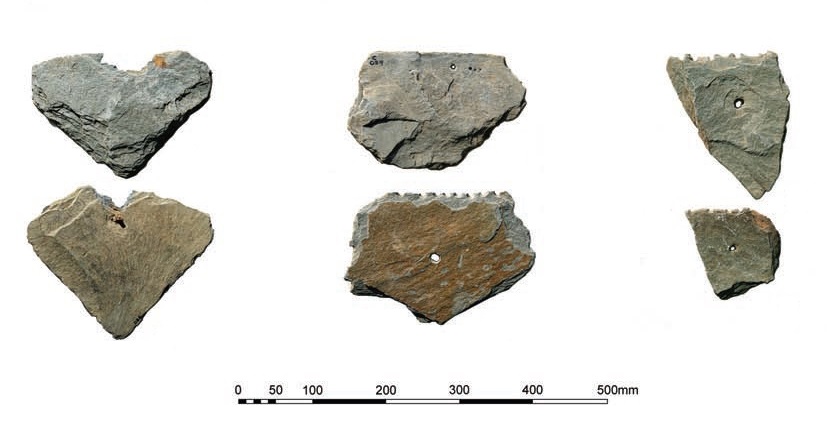

Roofing slates recovered from the Roman villa of Abermagwr. Original image in Davies and Driver, 2018. “The Romano-British villa at Abermagwr, Ceredigion: excavations 2010–15”

The Roman villa in Abermagwr, inhabited between the 1st and 4th century A.D. is in this district. A slate quarry has been found five kilometres from this villa, which provided the stone which the roofs were made from. The most important thing about this site is evidence of the production of standard models, for which a template (presumably metal) was used, serving as a guide to mark the slate’s surface.

Subsequently, the form was cut using an axe or similar tool, following the same process used in other slate producing areas until recently. The main form is hexagonal, with an approximate size of 30×30 cm, and more than one centimetre thick. Rectangular items and “rustic” forms, with similar dimensions and no defined shape, have also been found.

Several images of slate recovered from the Roman villa of Abermagwr. Original image in Davies and Driver, 2018. “The Romano-British villa at Abermagwr, Ceredigion: excavations 2010–15”

Installation and Roman models

This style of Roman placement must have been very similar to how it is installed nowadays in the traditional German school. The slates were fixed to the wooden roofing using nails, overlapping those which were underneath. The nails were made of wood or, more commonly, of iron, and many have been preserved until today. The holes for the nails were made with a tool with a quadrangular part, which gave the holes a square shape.

Reconstruction of a Roman slate roof using the items recovered in the excavation. Original image in Davies and Driver, 2018. “The Romano-British villa at Abermagwr, Ceredigion: excavations 2010–15

Another piece of evidence demonstrating that standardised models were produced is that the holes are always the same distance from the base, which was accomplished by using a tool of a similar size to the pic mesur, the Welsh name for the popular measuring stick used in all slate quarries until tape measures became popular.

Each piece of slate weighs approximately 2.7 kilograms, which would require a solid roof to support all this weight (greater than that of present-day slate). Furthermore, the slates usually have multiple additional holes as well as the main one, possibly due to the pieces being reused. It is also possible to observe marks left by the tools the slates were produced with, which is yet more evidence of regular production.

Pic mesur, stick for measuring the length of the slates.

Roman slates have been found in all areas of the Roman Empire, from the deposits already mentioned at Swithland, to Bermel (Mayen, Germany), Antwerp (Belgium) and Valencia do Sil in Valdeorras, Spain. All these areas have important slate deposits.

The network of roads built by the Romans, some of which are still in use today, allowed slate to be transported tens of kilometres, and there are even signs of its transport and trading across the English Channel. Belgian slate from what is now Ardennes was shipped with southern England as its destination, following a route which was kept active for many centuries.

Slate is not only an exceptional roofing material, it also has a centuries-old history. It has been used in essentially the same way since the Roman Empire, which is a guarantee proving its perfect adaptation to all types of buildings and architectural solutions.