Slate in Japan: a centuries-long story

Everyone who has ever visited Japan agrees on one thing; it is another world. Its culture, history and society are so different from Europe that visitors feel like they are on another planet. Everything, from simple everyday details to society itself, is different.

This also applies to traditional Japanese architecture, which uses light, flexible materials. The constant threat of earthquakes has created a special relationship between buildings and nature. Within such a different world, it is surprising and comforting at the same time to find something as familiar as roofing slate.

There are historical slate deposits in Japan on the Ogatsu peninsula (Sendai), which I had the chance to visit in 2019. These deposits have been exploited for centuries, mainly to produce inkstones.

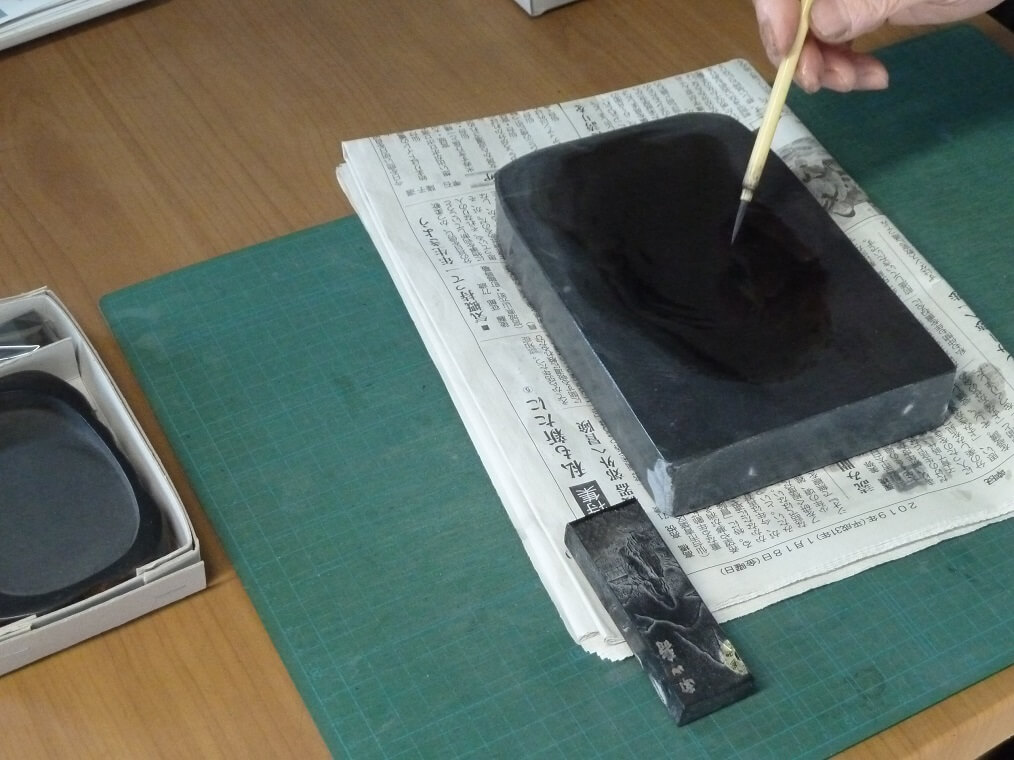

Demonstrating the use of an inkstone.

These are used to dissolve the ink sticks used for writing or drawing. A good inkstone needs to be easy to work with and to have a perfect finish for the ink stick to mix with the water properly. The rock that best meets these requirements is slate.

Ogatsu’s quarries were famed for the quality of their slate, of which there are two varieties, black and grey. The grey variety is most prized for making inkstones. The grey colour indicates a high quartz content, with this being a fairly abrasive mineral, which makes the ink dissolve more easily.

The black variety has less quartz and is much more cleavable, with a greater capacity to be opened in sheets. In other words, it makes an excellent roofing slate. Locals occasionally used this slate for their roofs over the centuries, but in a practically anecdotal manner.

In 1887, the German architects Hermann Ende and Wilhelm Böckmann were invited by the Japanese government to design new buildings to embody the new era Japan was entering. Japan had just come out the Tokugawa period, which had lasted since 1600, when it remained isolated and alien to the rest of the world, to dive into the modern era, in a new period known as the Meiji.

As good Germans, the two architects knew the beauty and versatility of slate roofs. When they had made sure that slate was available in Japan, they included it in several of their designs, with the Ministry of Justice being the most representative.

Old German-style slate roof in the Sendai area.

They introduced Japan to Central Europe’s traditional slate uses and designs, while a small industry was created in Ogatsu, production from which was absorbed by the works constructed in Tokyo.

Japanese architects learned the use of slate in these works. The most famous of these was Tatsuno Kingo, who designed Tokyo railway station, completed in 1914. This western-style building incorporates an extensive and elaborate Japanese slate roof that follows the classic French style.

Almost a century later, remodelling and maintenance work on the Tokyo station building considered replacing a large proportion of the slate roofing. The Ogatsu quarries had the material stored, ready for shipping, when the earthquake and subsequent tsunami of 2011 struck.

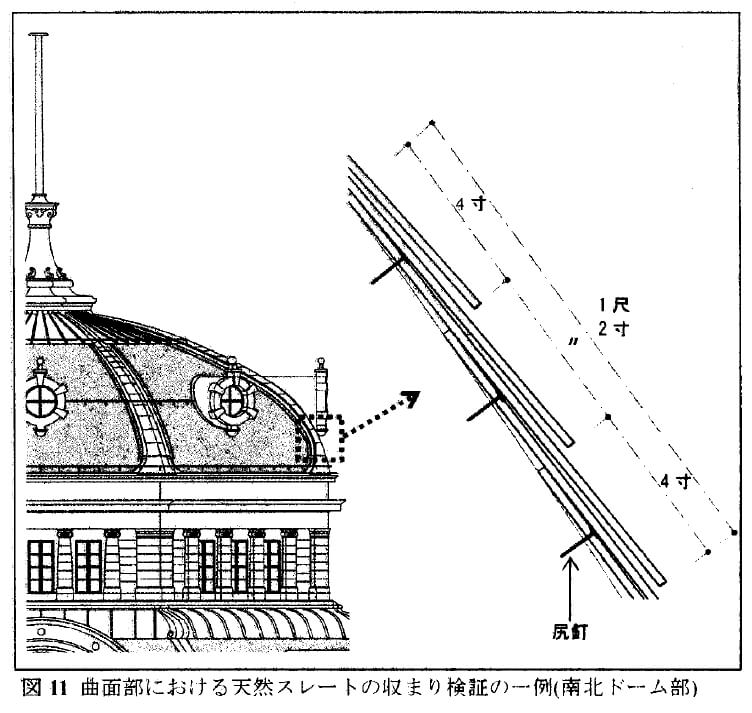

Part of the original Tokyo station roof design.

The tsunami hit the quarries, which stand a short distance from the sea, sweeping all the production away and virtually wiping the Japanese slate industry off the map.

As a result, the committee responsible for remodelling Tokyo station sought an alternative source of slate. One of the things that sets the Japanese apart is their great dedication to work, which borders on devotion, together with their perseverance the spirit of struggle.

It is not hard to guess where they found the slate that met their high quality standards. Just a few months after the disaster, a Japanese delegation visited CUPA PIZARRAS’ facilities, where they were able to see for themselves that Spanish slate is every bit as good at the Japanese.

Tokyo station was able to show off its new roof by the end of 2012. The Japanese slate industry is now slowly recovering in Ogatsu, but it is more focused on producing hand-crafted objects than on generating slate for roofing.

Producing this type of material is no longer feasible but due to the constant, high-quality supply of Spanish slate, Japan is slowly rediscovering the beauty of slate roofs, especially in urban areas.