Roofing slate in early times in Great Britain

The British Isles keep one of the most interesting slate architectural and historical heritage in the world. Since Prehistory, the many cultures that have populated the British Isles have used slates for lots of purposes: walls, hobs, tombs and gravestones, tools, engravings…you name it.

The first proper roofing slate shingles were found in the Roman settlements. Typically, Roman roofing slates had a rough diamond shape with a nail hole at the head. One of the most important Roman quarries for roofing slates is in Swithland, with a Cambrian green and/or purple slate, very similar to the Welsh slate, outcrops. The production was huge for the standards of that time. In Narborough, few miles south of these quarries, the excavations of a Roman villa in 1983 had a large number of roofing slates. Average dimensions for the shingles were between 7.5-11 inches (19-28 centimeters) for the height, and between 6.25-10.5 inches (16-27 centimeters) for the width.

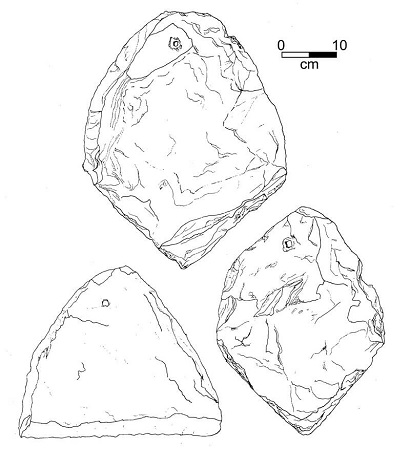

Roman slates: Some drawings of Roman slate shingles recovered from the excavations of the Roman vila of Narborough.

Image from The Roman Swithland Slate Industry, 1988, by Alan McWhirr.

Once the Romans left the Isles, in the 5th century, the roofing slate tradition was forgotten, or at least there are no records of it. Saxons did not use slate very much, they preferred to thatch roofs. Stone in general was reserved for churches. However, this changed by the 11th century, with the arrival of the Normans. The Normans brought a new architectural style, in which castles and fortifications played an important role. There is a mention in the Pipe Rolls (historical record accounts) to a roofing slate quarry somewhere in south Devon, which is the first explicit mention to the industry. The word “slate” is believed to come from the Old French escalate, meaning fragment, from the verb esclater, to shatter. This term was used together with the Latin term lapid tegul, where lapid means stone and tegul tile or shingle.

In the 12th century we find the next historical reference, which is the re-roofing of the Conwy and Caernarvon castles, both in Wales. Only the most prestigious buildings had slate covers. At that time, roads were virtually nonexistent, and land transportation was very hard and difficult, so boat transportation was preferred when possible. In the 70s of the last century, a vessel wreckage was discovered in the Menai Strait tidal waters in Wales. The wreck of Pwll Fanog was a slate cargo with about 23000 slates. Tool marks on the slates show that they were split with a gouge instead of a chisel, which is the normal practice since about 1730. The estimated age of the vessel is from the 13th century.

Wreck slates: Slates recovered from the wreck of Pwll Fanog.

Image from The Pwll Fanog wreck – A slate cargo in the Menai Strait, 1979, by Cecil Jones

The next historical reference to roofing slate (and mentioned in almost every publication I’ve read for this post) deals with the stay of Edward 1st (1272-1307) on Nantlle, in the 13th century. He seems to have slept under a slate roof, which was unusual enough to be recorded. So we can infer that not many houses had slate roofs and that probably there was a slate quarry in the surrounding areas. Jope, in his work of 1954 entitled The use of blue slate for roofing in Medieval England, writes

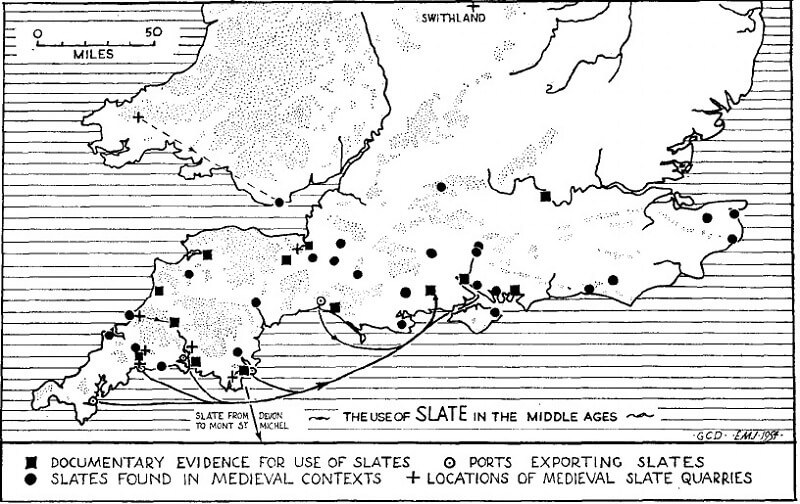

The Pipe Rolls show that many thousands of slates were already coming to Southampton, Winchester, and Porchester from the Devon ports of Dartmouth, Totnes, and Plympton in the late 12th century, and this trade continued through the middle ages, Dorset and Cornwall also supplying slates later.

There is much evidence of an intense maritime trade of roofing slates, not just between Britain’s ports but with the continent. For example, Jope mentions the finding of a green roofing slate in the medieval village of Hangleton, which probably came from Fumay, in the French Ardennes. This draws a rather complex story of medieval trade of roofing slates. Jope also points out that

The use of blue slates and their distribution over a wide area seems to be part of a general movement during the 13th century towards more robust and less inflammable roofing, as suggested by, for instance, the London building regulations of 1212.

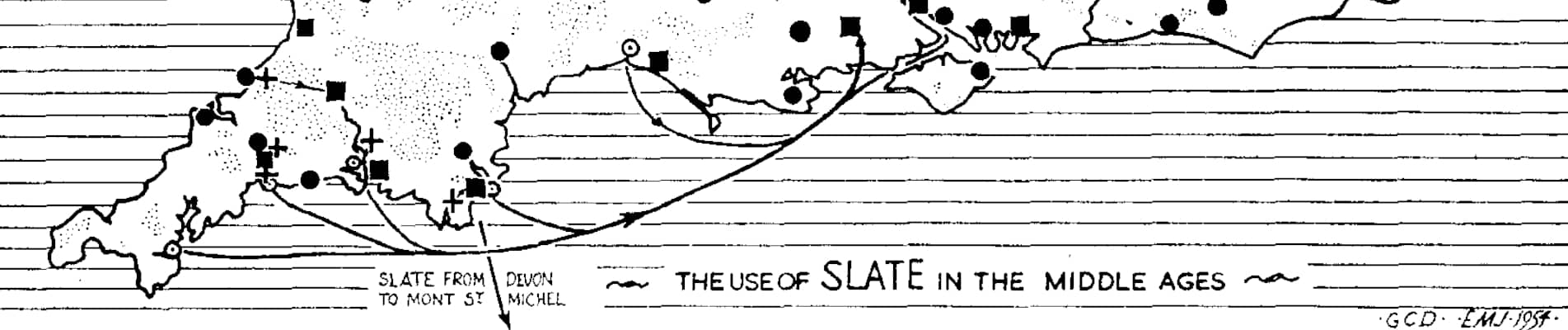

Map summarizing the evidence for the use, quarrying, and transport of blue slates in the south ofEngland during the Middle Ages. Rivers are shown only in so far as there is evidence for their medievalnavigability. Land over 500 ft. is stippled

Photo from: Jope, E., & Dunning, G. (1954). The use of blue slate for roofing in medieval England. The Antiquaries Journal, 34(3-4), 209-217. doi:10.1017/S0003581500059886

The first record to date of slate quarry ownership in South Devon states that, in 1439, the Earl of Warwick, Richard Beauchamp had “diverse quarries of stone suitable for roofing”. In 1570, Sion Tudor (or Tudur, dependings on the source), a Welsh poet (or bard, as he claimed), sent a poetical letter to the Dean of Bangor, asking him for a load of roofing slates from the Caehir quarry with the purpose of covering his house.

As in the rest of the European countries, roofing slate quarries were in the hands of landowners (nobility and church). Quarries were then rented to the workers, which had to pay rent. There has been roofing slate industry in Wales and England since the 12th century. On the other hand, in Scotland it was not present until the 17th century when the Easdale and Ballachulish quarries were opened.

There are still many things to say about the history of roofing slate in Britain. Please notice that I have not mentioned the Penrhyn quarries, or the use of roofing stones (roofing sandstones and limestones). These questions will be explored in future articles.

This article is part of a series written by the Geologist and slate consultant Víctor Cárdenes, where you can find interesting features about natural slate. If you have enjoyed this article, you can read also about the roofing slate standards, a comparison between Spanish and UK slates and learn some facts you didn’t know before.